There’s a lot of misinformation, speculations, and rumors regarding how the legality works with regards to simulated games. All the information below is referenced and based on facts from official .gov websites. I hope this clears up any misunderstandings. If you actually read through all of this, then congratulations - you now have some decent knowledge on copyright laws with regards to game development.

Q: What is a C&D?

A: A cease and desist letter, also known as infringement letter or demand letter, is a document sent to an individual or business to halt purportedly unlawful activity (“cease”) and not take it up again later (“desist”). The letter may warn that if the recipient does not stop specified conduct, or take certain actions, by deadlines set in the letter, that party may be sued. A holder of IP (Intellectual Property) right such as copyright, trademark, or patent may send this letter. The letter can sometimes be a licensing offer or an explicit threat of a lawsuit.

Q: Why would a game get a C&D?

A: A C&D letter can state that there has been copyright infringement, trademark infringement, or patent infringement or any combination. Usually, a simulated game will contain copyrighted artwork which can include pictures of cards, logos, icons, etc. If a copyright holder believes they are losing profits due to a third-party product, then they are more likely to send a C&D.

Q: What does copyright exactly protect?

A: “Copyright does not protect the idea for a game, its name or title, or the method or methods for playing it. Nor does copyright protect any idea, system, method, device, or trademark material involved in developing, merchandising, or playing a game. Once a game has been made public, nothing in the copyright law prevents others from developing another game based on similar principles. Copyright protects only the particular manner of an author’s expression in literary, artistic, or musical form.”

http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl108.pdf

Note that the above definition is specific for creating games.

Only the owner of copyright in a work has the right to prepare, or to authorize someone else to create, an adaptation of that work . The owner of a copyright is generally the author or someone who has obtained the exclusive rights from the author. In any case where a copyrighted work is used without the permission of the copyright owner, copyright protection will not extend to any part of the work in which such material has been used unlawfully. The unauthorized adaption of a work may constitute copyright infringement.

https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ14.pdf

Here we see that a “derivative work” is not allowed without the copyright holder’s permission. So what is considered a derivative? A game itself is made up of several components - pictures, rules, and mechanics. The pictures of a game, the field, pieces, design, etc. are copyrighted. The rules and mechanics of a game cannot be copyrighted. Hence, even if a game is developed which is an adaptation of a pre-existing game (ex. Yu-Gi-Oh), it can only infringe copyright if that game contains adaptations of copyrighted material. If it does, then those adaptations are considered “derivative works”. The copyright holder cannot prevent a developer from creating a game that has no copyrighted material to begin with even if the rules and mechanics of the game are similar.

Q: Then what protects the rules and mechanics of a game?

A: That can be covered by a patent . The exclusive right granted to a patentee in most countries is the right to prevent others, or at least to try to prevent others, from commercially making, using, selling, importing, or distributing a patented invention without permission . The patent holder can grant a license to a party to sell their product. The license agreement states the percent of total profit (usually 1-2%) or royalties that must be paid to the patent holder. A patent is territorial , so it only protects it in the country where the patent was filed. Konami does not own any patents for the rules and mechanics of Yu-Gi-Oh. Note that manual simulators don’t have mechanics and hence can never infringe these patents.

Q: What’s a trademark?

A: “A trademark is a word, phrase, symbol or design, or a combination of words, phrases, symbols or designs, that identifies and distinguishes the source of the goods of one party from those of others.” A trademark is territorial , so it only protects it in the country where the trademark was registered. - http://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/basics/trade_defin.jsp

Q: Can a copyright holder in one country send a C&D for something in another country like US?

A: Copyright holders have the right to file for copyright infringement in the US and many other countries. This is because of international copyright treaties that the US and several other countries have signed. There are only a few countries that have not signed these treaties: Afghanistan, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Iran, Iraq, and San Marino.

http://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ38a.pdf and http://www.copyright.gov/fls/fl100.html

Q: So why doesn’t a copyright holder C&D everyone?

A: To put it simply, it is bad for business. There is a beneficial effect of having fans build sites, curate libraries of resources and constantly talk about and consume your content. It’s free marketing. Whether a copyright holder chooses to exercise their right is essentially a cost/benefit analysis.

In addition, websites like Wikia that provide information for teaching purposes and are non-profit classify under “fair use”.

Q: What is “fair use”?

A: Section 107 of the Copyright Act defines fair use as follows:

“ [T]he fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include –

- t he purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole;

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work.”

Additionally, “transformative” uses are more likely to be considered fair. Transformative uses are those that add something new, with a further purpose or different character, and do not substitute for the original use of the work.

For more information, read here: http://fairuse.stanford.edu/overview/fair-use/what-is-fair-use/ or http://www.dmlp.org/legal-guide/fair-use

Q: Does taking images from a wiki mean it’s fair use?

A: No, it would not! Taking images from a source that has been classified as “fair use” does not automatically mean that your project is “fair use”. Fair use is determined by the “use” of the copyrighted content. In this case, the content is not being used as parody, commentary, criticism, and teaching. For example, quoting a few lines from Bob Dylan’s song in a music review constitutes as fair use.

Q: Is fanart fair use?

A: Pop culture is prevalent today in modern times. There are conventions for almost everything movies, books, tv shows, anime, etc. At these conventions artists gather and do sell their work which can be in the form of posters, drawings, fan art, statues, etc. All of this has been happening for years. This all falls under fair use or does it? The answer is that it depends. The only way to objectively answer this is to look at similar cases in the past and see how the court ruled.

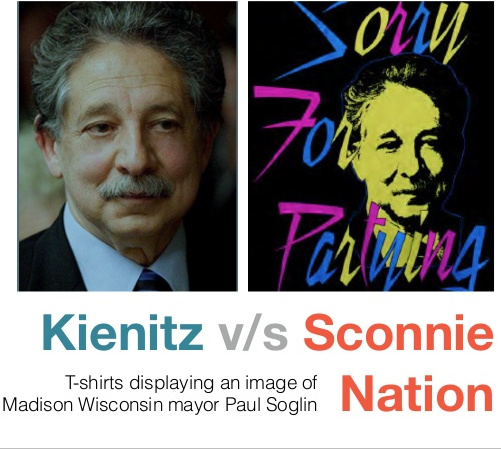

The case of Kienitz v Sconnie Nation LLC, 766 F.3d 756 (7th Cir. 2014) gives us an example scenario. In this case, a photo of a Wisconsim mayor was put on a T-shirt and sold to raise money for an event opposed by the mayor. The US Court of Appeals (only below the Supreme Court), ruled that the photo on the T-shirt was altered or “transformed” sufficiently that the background was removed, text was added, and only a green outline of the mayor’s smile remained similar to the smile of a Cheshire cat. Therefore, this fell under fair use. This case is probably the best reference for lawyers and defendants to defend fair use of fan art.

How much of a photo do you need to alter to avoid copyright infringement? Hint: Cheshire Cat

Let’s look at another case, a more popular one where a photograph of ex-President Obama was taken and used to make a poster - Fairey vs Garcia. In this case, Shepard Fairey, a graphic artist, used Photoshop to modify the picture of Obama on the internet, to create a poster, sell it, and distribute it for free as well. Garcia was the original photographer who took a snapshot of Obama at a briefing. This was a Supreme Court case with the conclusion that neither party surrendered. However, Fairey did have to obtain a license from Garcia for future works.

https://cyber.harvard.edu/people/tfisher/IP/Hope_Poster_Case_Study.pdf

Note that in both of the above cases, the work was commercialized and hence, the fair use defense was weaker. When it’s commercialized, one has to prove that the work is “transformative” to a significant degree from the original. Contrary to popular belief, copyright infringement occurs whether or not a product is free or not.

Q: Is YGOPro and its derivatives illegal?

A: The source code for Ygopro simulators does not violate any copyright, trademark, or patent laws. It is open sourced on github and under the GPL v3 (General Public License) which gives end users the freedom run, modify, share, and distribute it. “Fair use” can also be used as a defense if needed for open sourced code since it is used for teaching and is non-profit. The server however still violates copyright because the pics are downloaded automatically in some YGOPro simulators. Due to this, even if the client itself did not come with pics, it is still connected inherently to a server that has copyrighted material. Not all YGOPro simulators face this problem though. The YGOLite game does not come with any pics and does not download any pics automatically from any server. Instead, users have to obtain the pics themselves and store it client-side. YGOLite is the only Yu-Gi-Oh simulator to be approved in the official iOS appstore due to this. (Previous versions of YGOLite were rejected if they came with pics or auto-downloaded from a server.) If card art were to be fan arts or modified to a degree that is transformative, then even if the client downloads those arts automatically from a server, it is now fair use.

Next, are patents. Since YGOPro is an automatic simulator, the mechanic is automated. The mechanic is patented and hence if the game is generating profit, it will violate patents which are owned by Wizards. This means if Wizards wanted to enforce patents, then they can. If they do not grant a license, then the game cannot be commercialized under any circumstances. If they do grant a license, a small percentage (usually 1%) of the profits to go to Wizards. However, these mechanics come from the scripts which are instructions to the game as how that card is used. The scripts are also open sourced and on github, so it is legal to distribute it via github. At this point, the scripts are now prior art and can’t be protected by a patent. An example is if a pirated song is being played on an mp3 player. The mp3 player does not violate any laws. In this case, YGOPro is the mp3 player while the pics are the song.

Q: Who owns the patents, trademark, and copyright for Yu-Gi-Oh?

A: Before we answer that question, one must understand what Yu-Gi-Oh is. There are several different components – the manga, the anime, the toys, the trading card game, and the movies.

Trading Card Game - The patents with regards to trading card games, most of the mechanics, and gameplay was filed in 1996 by Richard Garfield (inventor of Magic the Gathering) and Wizards of the Coast (the company that licenses MTG and is owned by Hasbro). Konami pays royalties to Wizards for profits made from the Yu-Gi-Oh card game. You might have thought that Kazuki Takahashi, author of Yu-Gi-Oh, owns the patents, but that is incorrect. Kazuki Takahashi is the author of Yu-Gi-Oh and while he did create the rules and gameplay, he cannot patent it because most of these mechanics exist in other trading card games which Magic the Gathering was the pioneer of. Kazuki Takahashi instead owns the copyright.

-

Patents by Wizards and Richard Garfield related to card games (not comprehensive)

-

Patents by Konami with related to card games (not comprehensive)

- www.google.com/patents/EP1700627A4

- www.google.com/patents/US7371165

- www.google.com/patents/US7144013

- www.google.com/patents/US20040036220

- www.google.com/patents/EP1700627A4

- www.google.com/patents/US20070273096

- www.google.com/patents/US8409016

- www.google.com/patents/US20070082723

- www.google.com/patents/US20070045962

- https://patents.google.com/patent/US7144013B2/

The artwork of the cards belong to Studio Dice, which is a company owned by Kazuki Takahashi. This company has artists that draw the art that appears on the cards. As of 2020, “Studio Dice” now appears at the bottom of the card instead of “Kazuki Takahashi”.

The license to distribute the Yu-Gi-Oh trading card game could have gone to Wizards of the Coast, but at that time, they chose to license with Star Wars instead. The license to distribute the Yu-Gi-Oh trading card game instead went to Upper Deck, who distributed it in the US from 2002-2008. Since 2008, Konami now has the license to distribute the trading card game all across North America.

The manga – The author of the original manga is Kazuki Takahashi. Authors don’t patent stories, they claim copyright. Kazuki Takahashi owns the copyright for the Yu-Gi-Oh manga and story as well as the trademark name and has licensing agreements with Konami so that he gets a portion of the profit from Yu-Gi-Oh products sold.

Kazuki Takahashi first wrote the Yu-Gi-Oh manga in the Shonen Jump in 1996. Hence, Shueisha which owns the Shonen Jump is responsible for publishing the manga, graphic novels, and any literary work regarding Yu-Gi-Oh. Shueisha signed agreements with Kazuki Takahashi as most authors do when they want their work to be published.

The anime and movies – The first ever anime was in 1998 in Japan and it was animated by Toei Animation. This is what people refer to as “Season 0”. This was never released outside of Japan, but people can download it from the net.

Nihon Ad Systems (aka NAS) owns the copyright for the TV anime for Yu-Gi-Oh and also the copyright for the artworks. NAS animated the Yu-Gi-Oh series in 2000 in Japan. Then they also gave rights to 4Kids to animate Yu-Gi-Oh in North America. NAS filed a lawsuit against 4Kids in March 24, 2011 accusing them of underpayments (lying about actual profits made from Yu-Gi-Oh). They terminated their agreement with 4Kids. Konami then bought 4Kids and renamed it to 4K Media Inc.

As of July 21, 2019, the copyright for production of Yu-Gi-Oh Sevens belongs to Bridge Studios.

Toei Animation is also involved with producing many of the movies but they have agreements with NAS and Konami to do so.

Toys and other merchandise – Profits made from selling merchandise and toys is made by Konami. A portion of that profit goes to Kazuki Takahashi as well as the companies that manufacture the toys and the distributors who then sell them.

============================================================

Legal Defense for Duelists Unite

Introduction:

Duelists Unite has developed a non-commercial, fan-made digital card game that simulates the experience of playing Yu-Gi-Oh! The game is free to play, devoid of advertisements, and includes links directing users to purchase official Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, thereby indirectly benefiting Konami. This defense argues that the use of Yu-Gi-Oh! card artworks in the game constitutes fair use under U.S. copyright law.

Fair Use Analysis

1. Purpose and Character of the Use:

-

Non-Commercial Nature: The game developed by Duelists Unite is entirely free and contains no advertisements. This absence of commercial intent supports a fair use defense, as non-commercial uses are more likely to be considered fair.

- Precedent: In Blanch v. Koons (2006), the court ruled that Jeff Koons’ use of a photograph was fair use due to its transformative nature and the lack of commercial exploitation.

-

Transformative Use: The game provides a new, interactive experience that educates players about Yu-Gi-Oh! and allows them to engage with the franchise in a unique way. This transformative use adds new expression and meaning to the original artworks. Additionally, some parts of the game take the original artworks and remove the background to create transparent PNGs, acting like holograms or projections, further transforming the original work.

- Precedent: In Cariou v. Prince (2013), the court found that Richard Prince’s use of photographs was transformative and constituted fair use because it added new expression and meaning.

-

Educational Purpose: Websites like Wikipedia and Wikia showcase all the artworks of Yu-Gi-Oh! cards and are able to use these artworks under fair use because of their non-profit and educational purposes. Similarly, Duelists Unite’s game serves an educational purpose by teaching players about the Yu-Gi-Oh! card game.

- Precedent: In Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. (2006), the court ruled that the use of concert posters in a biography was fair use because they were used as historical artifacts within a larger educational work.

2. Nature of the Copyrighted Work:

- The original artworks used in Yu-Gi-Oh! cards are creative works protected by copyright. However, fair use can apply even to highly creative works, especially when the use is transformative and non-commercial.

- Precedent: In Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith (2019), the court ruled that Warhol’s use of a photograph was transformative, adding new aesthetic and meaning to the original work.

3. Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used:

- The artworks used in the game are a small part of the overall experience, which includes new characters, storylines, and mechanics created by Duelists Unite. The use of these artworks is limited and necessary to achieve the transformative purpose of simulating the Yu-Gi-Oh! card game.

- Precedent: In Bill Graham Archives v. Dorling Kindersley Ltd. (2006), the court ruled that the use of concert posters in a biography was fair use because they were used as historical artifacts within a larger educational work.

4. Effect of the Use on the Potential Market:

- The game does not compete with Konami’s official products. Instead, it promotes Konami’s products by including links for players to purchase official Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, potentially increasing Konami’s sales. This indirect benefit to Konami supports the argument for fair use.

- Precedent: In Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation LLC (2014), the court found that the use of a photo on a T-shirt was transformative enough to constitute fair use, highlighting that the use did not harm the market for the original work.

Additional Relevant Precedent Cases

-

Fairey v. Garcia (2009)

- Summary: Shepard Fairey used a photo of President Obama to create the iconic “Hope” poster. Although the case was settled, it highlighted the complexities of transformative use and fair use in artistic works.

- Relevance: This case illustrates the boundaries of fair use when using photographs and supports the argument that Duelists Unite’s use of Yu-Gi-Oh! artworks is transformative.

-

Sony Computer Entertainment America, Inc. v. Bleem, LLC (1999)

- Summary: Bleem created a software emulator for Sony PlayStation games. The court ruled in favor of Bleem, noting that the emulator was transformative and did not harm the market for PlayStation games.

- Relevance: This case supports the argument that creating a simulator can be considered fair use, especially when it does not harm the market for the original product.

-

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc. (1994)

- Summary: The Supreme Court ruled that 2 Live Crew’s parody of “Oh, Pretty Woman” was fair use, emphasizing the importance of transformative use and the purpose and character of the new work.

- Relevance: This case reinforces the importance of transformative use and can be cited to show that Duelists Unite’s game adds new meaning and context to the original artworks.

-

Perfect 10, Inc. v. Amazon.com, Inc. (2007)

- Summary: The court ruled that Google’s use of thumbnail images in its search results was transformative and constituted fair use, as it provided a new purpose by improving access to information.

- Relevance: This case demonstrates that even commercial entities can claim fair use for transformative purposes. Duelists Unite’s non-commercial and transformative use of Yu-Gi-Oh! artworks in their game further strengthens this defense.

-

Castle Rock Entertainment, Inc. v. Carol Publishing Group, Inc. (1998)

- Summary: The court ruled against the use of Seinfeld trivia books because they did not add any new transformative value but simply repackaged original content.

- Relevance: This case highlights the need for significant transformation, which Duelists Unite’s game achieves through its new interactive context and educational purpose.

Emphasizing the Non-Commercial and Transformative Nature

1. Non-Commercial Intent:

- The game is free and lacks advertisements, underscoring the lack of profit motive. This non-commercial nature is a strong point in favor of fair use.

2. Promotion of Konami’s Products:

- The game includes links directing users to purchase official Yu-Gi-Oh! cards, benefiting Konami by driving sales and promoting their merchandise.

3. Community Engagement and Educational Value:

- The game fosters a positive community around the Yu-Gi-Oh! franchise and provides educational value, aligning with the principles of fair use. Active community engagement and feedback also enhance the game’s transformative nature.

4. Comparative Examples:

- Compare the game to chess simulators, which are widely accepted and non-commercial, arguing that Yu-Gi-Oh!, as an established game, should similarly allow for non-commercial simulations that promote the game.

Conclusion

By leveraging these precedent cases and emphasizing the non-commercial, transformative nature of Duelists Unite’s game, we can build a compelling legal defense. This approach demonstrates that Duelists Unite’s game falls within the bounds of fair use and should be legally permissible.

This comprehensive defense incorporates the principles of fair use, supported by relevant precedent cases, to argue that Duelists Unite’s game should be allowed to continue legally.